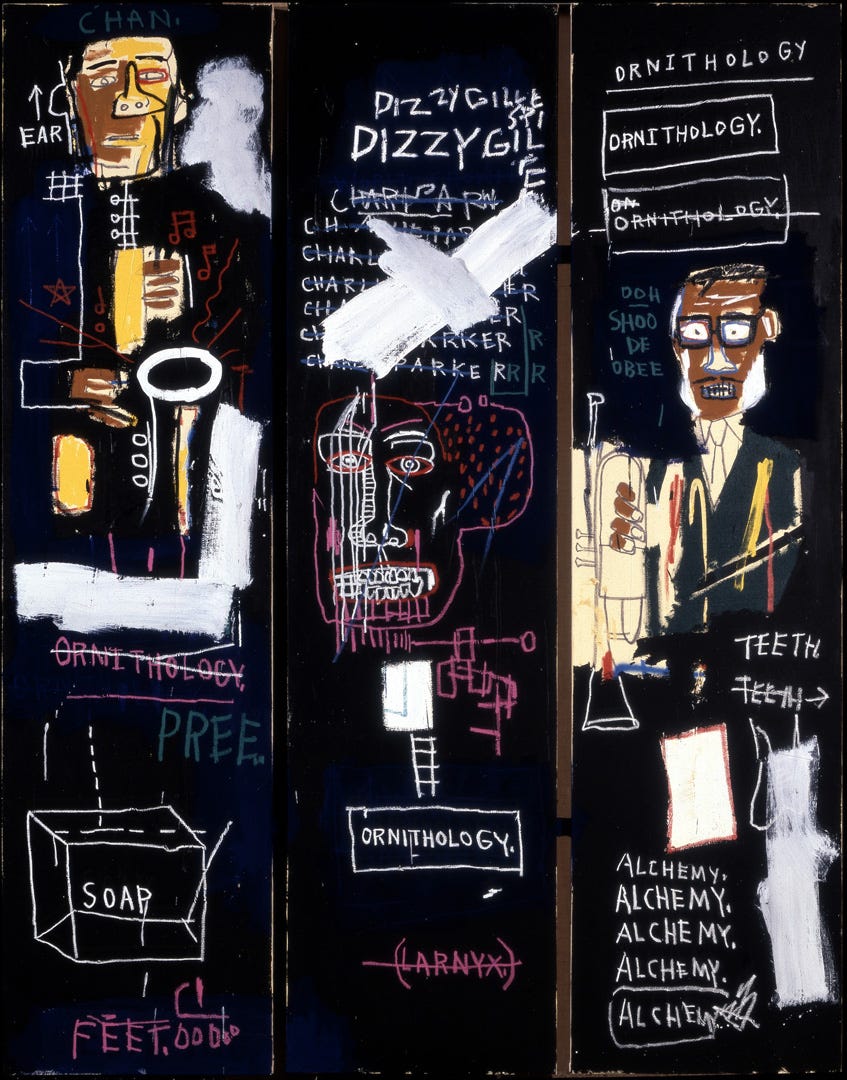

Death of a Jam, Part 1

A post-mortem for a short-lived enterprise and a deeper examination of the present state of jazz jam sessions in Glasgow.

It didn’t take long for an exciting new development in Glasgow’s jazz scene to fizzle out. Jazz at the Basquiat, a new, biweekly jam session at Bar Basquiat near Charing Cross, lasted all of five dates before being suspended indefinitely. Jazz is defined by transience and necessitates adaptability, often in the face of proclamations of the form’s demise. Sessions, settings, entire scenes come and go according to the whims of the pub economy. Jazz will persist, as it always does. But with the long-running weekly jams at Finnieston staple The 78 also shuttering over the summer and leaving sessions at The Butterfly and the Pig seemingly standing alone, opportunities for public, low-stakes jazz in Glasgow (for players and listeners alike) appear to be at a lull.

Drummer Nemo Ganguli, a University of Glasgow student and the event’s organiser, pitched Jazz at the Basquiat as a self-sufficient enterprise, needing only a venue and compensation for the hosting musicians. Yet despite being framed as an investment that would require time and patience to gather a following, the bar cancelled the series after just two months. Ganguli cited the bar’s finances and location, as well as a lack of promotional effort, as the chief culprits behind the cancellation. An employee at the Basquiat related a similar story, claiming that, after paying the house band, profits from the evening of the final event were negligible. The employee added that the Tuesday night crowd was simply insufficient, noting the dearth of student attendance. When pressed about the possibility of moving live music to a weekend in place of some of the regular DJ nights, the employee changed the subject.

Jam sessions are a central component of many music scenes, but they characterise jazz more so than any other style. Jams provide a space for local veterans to hang out, experiment with ideas in a live setting, and play in configurations they may not otherwise explore. Jams also enable scene newcomers to introduce themselves and make connections in pursuit of further playing opportunities -- I took this approach upon moving to Glasgow. It is primarily for the latter reason, I believe, that regular, public jam sessions are so vital. Without a natural inflow of new talent, a scene will stagnate, cease to attract players, and gradually diminish to a core of subsistence rather than expression. The jam session is a space for that unshackled expression as well as a signpost pointing toward more music.

What Glasgow does have is a natural source of new talent. The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) -- specifically its jazz course -- supplies the city with an annual stream of young musicians from around the world and deposits them into the musical landscape for a minimum of four years. While the presence of a jazz school in a cultural centre is hardly unusual, what makes Glasgow unique is a combination of two chief factors: RCS hosts the only dedicated jazz degree in the region; and Glasgow is a city in which graduates increasingly want to remain. In the US, at least as far as I am aware, this confluence does not exist. For instance, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago are each home to several longstanding and renowned undergraduate jazz programs, and serve as magnets for musicians throughout the country. By comparison, Glasgow-esque cities in terms of jazz educational opportunities, such as Denton (University of North Texas), Washington, D.C. (Howard University), and even Boston (Berklee, New England Conservatory) have organic scenes of their own but lose many young players to New York or LA following graduation. For a time, Glasgow was clearly subordinate to London in terms of UK jazz, but as RCS jazz and its products continue to grow in stature and draw national coverage, Glasgow (long the Scottish hotspot for music) is strengthening its case as a legitimate competitor. It just needs time. After all, the RCS jazz course debuted in 2009 and arguably only recently produced its first bonafide star in pianist Fergus McCreadie.

In other words, Glasgow’s jazz scene--praised as youthful, dynamic, and developing--is now constructed primarily around people from one small university course. This concentration has led to the development of a tight-knit group of musicians and even a ‘Glasgow Sound’ in a remarkably brief period of time. It is wonderful to witness and exhilarating to enter into. It is also weird! RCS jazz nurtures talent and fuels the external scene, but it also enables musicians to meet and play with one another before ever venturing into the outside arena. On the one hand, facilitating connections is why music programs exist, and populating a jam with experienced collaborators can create a more enjoyable listening experience. On the other hand, it becomes possible that ‘outsiders’ attempting to break in may acutely sense these pre-existing bonds and struggle to form their own in the absence of mandated introductions.

The importance of the jam session as an alternative avenue is heightened in an environment such as this. And while recent steps backward should not overshadow decades of jamming history, we must not take the wonder of jam sessions for granted. Jazz at The 78 ran for fifteen years and survived the pandemic, yet opted to shut down rather than scale back to monthly events as the bar looked to cut costs amid the UK’s cost of living crisis. Drummer/producer/audiovisual artist Stuart Brown told me that he, alongside Euan Burton and Tom Gibbs, created Jazz at The 78 in response to a wave of Scottish jazz musicians who returned to Glasgow after studying in Birmingham and found no regular hang. The jam was packed every Sunday, said Brown, and “made the scene feel less separated”, both in terms of age-stratified peer groups and location. Part of what made the 78 jam work, Brown continued, was that it centred around a young, ambitious group of players, just like the current generation of RCS progeny. It was also, at least for a time, the only show in town for people wanting consistent, quality jazz. Both situations have changed, Brown acknowledged. “We were younger when we started running that night”, he said. “People want to be around their own age group.” The 78 attracted younger audience members -- particularly students from the nearby University of Glasgow (UofG) -- but there was a perception, according to Ganguli, that it was somewhat “old school” and “nearing the end of its lifecycle”. Sustaining Jazz at the 78 for fifteen years is an extraordinary achievement, but its demise is also a stark reminder that, as organic and communal as these jams are, they remain at the mercy of their hosts, who are themselves subject to the instability of the hospitality business.

In contrast, crosstown sessions at The Butterfly and the Pig roll on, packing the house during term time and featuring rotating house bands of Glasgow’s best and brightest. These sessions have long been managed by people with RCS connections (at present, saxophonist and recent graduate Sean Megaw), and as such each week’s host is more often than not a current or former student of the conservatoire. The Buttpig jams, as they are affectionately known, share similarities with The 78’s sessions: it sprung up roughly fifteen years ago, has a large student audience, and has historically relied on word-of-mouth marketing. Butterfly and Pig, however, sits on Bath Street in the city centre, surrounded by restaurants, bars, and clubs, and just a few blocks from both RCS and the Glasgow School of Art (GSA). The pub runs a consistently diverse array of music events throughout the week and has developed a reputation as an arts bar independent of jazz events. And while RCS jazz students were a fixture at The 78, Butterfly and Pig’s convenience and relative affordability speak to the greater student demographic. Megaw notes that, unlike UofG, neither RCS nor GSA have a dedicated student union, forcing students to identify external social locations. From this confluence of factors has emerged “a cult following” for the Buttpig jams, built on communal energy and the appeal of the unknown.

One gets the sense while at The Butterfly and the Pig that the Wednesday night jazz jams have evolved beyond the music. The performance is always present and central, but the layout of the room and the size of the crowd ensure that some attendees are unable to see the stage. The barrage of pub conversation fills every gap in the music, and even on freezing nights the partially-sheltered patio out front is busy with people seeking refuge from the suffocating interior. The jams themselves are surprisingly curt: by the time the house band has finished their opening set, come off their break, and played a final tune to open the floor, there is sometimes less than an hour remaining for open jamming before the bar cuts things off at 11:30. This balance is part of a strategy to provide high-quality jazz without overwhelming listeners with on-stage chaos and overly-intellectual shredding. Listening to Megaw’s playing makes his respect for and dedication to the bebop tradition immediately clear, but he is likewise cognisant of modern audience dynamics and the need to adapt. “You’re not just playing”, he said. “It’s a performance.” There’s a buzz in the room — groups lounging on leather couches, students in dark sweaters sketching musicians, the feeling that everyone knows everyone else, swingin’ standards — that you don’t get elsewhere in the city, and extended pauses or dips in cohesion can feel like a risk for those in charge. Straight-ahead jazz, Megaw admits, isn’t “the hip new thing” anymore, but it clearly still has a place in youth culture. Leaning into the ‘speakeasy’ setting and more performative aspects to preserve the fundamental structure is by no means a bad thing.

Monthly evenings with collectives Supersonic and Glitch41 drag the jam session format further into the present. Flashy sets of modern popular standards flow into jams where audience members join the band to improvise over invented dance grooves. These nights live in dance halls and rock clubs, and are carried by relentless and inventive marketing (Supersonic leader Dillon Barrie’s name came up in nearly every conversation I had for this piece; Ganguli and Brown lauded his creativity and drive, while Megaw referred to him as “a great mind”). It is ceaselessly thrilling to see local performers iterate so creatively on the jam session form while preserving the essential spirit of improvisation at its core. But Supersonic and Glitch41 exist in a musical tradition fundamentally divergent from straight-ahead jazz; one that draws on a rich diversity of sources, from dub to pop, and excels at breaching a young, modern audience. I will not be surprised if such events prove to have illuminated the mainstream future of Glasgow jam sessions, and it will be fascinating to witness how they and their component artists evolve. Still, ‘improvised groove music’ doesn’t quite scratch the jazz itch. Despite many overlaps in both ethos and personnel, these are different spaces for different things. I don’t think that anyone is advocating for the replacement of one with the other, but these things can happen slowly, and we would be remiss not to take extreme care to preserve the jazz jam now, while fragments of it still thrive.

Part two, in which I look beyond Glasgow and propose several alternatives to and aspirations for the state of local jazz, will arrive next week.

A really brilliant piece. Long live jazz!